This week I attended a workshop on Languages and Education in Indigenous Australia, hosted by the Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language at ANU. It was an interesting counterpoint to the previous week’s event hosted by First Languages Australia in Adelaide, which focused on the implementation of the draft framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages in the Australian Curriculum and what was happening in various contexts. The Canberra event looked at language acquisition in Indigenous contexts more broadly, including children learning English and contacts languages as well as their own language.

We heard presentations from a number of CoEDL researchers, including work on individual differences in language development, the role of symbolic play in language acquisition, some research into first language acquisition in Papua New Guinea, and the role of prosody and other phonological features in language acquisition in Malay and Barunga Kriol. We heard about projects in communities such as Wadeye and Kukatja where English is not spoken much outside the classroom, and in communities such as Jilkminggan and Gunnedah where traditional languages are no longer strong. We explored some of the challenges inherent in language revival programs, the role of Indigenous language in the Maths classroom, the effects of otitis media on Indigenous children’s language acquisition, how print literacy may impact learning Standard Australian English, the impact on children in remote Indigenous communities of NAPLAN testing and English language assessment more generally, and the ‘affordances’ of language programs in the context of the Australian Curriculum. It was also interesting to hear about some contexts that don’t neatly fit into general approaches to language acquisition, such as the complex linguistic ecology of communities where neither Standard English nor traditional languages are spoken or taught, and what that means for contact languages such as Kriol, and literacy practices outside of the school in endangered language communities.

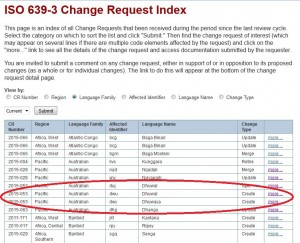

A public event gave opportunities to share about wonderful work on the Warlpiri theme cycle and the investments in education made in Warlpiri communities, then discussion and demonstration of some language apps for Indigenous languages. These included community involvement in the development of Memrise for languages of Tennant Creek, and making short videos using Powtoon for Gamilaraay, some other potentially useful game apps, innovative means of testing phonological awareness in Yolngu Matha, and the incredible work that’s gone into the creation of the world’s first Australian indigenous language app Tjinari in Ngaanyatjarra.

The final afternoon was spent brainstorming the issues raised throughout the previous day and a half, focusing on:

- where we want education of Indigenous children to be in five years time;

- how does our existing research fit into that

- how can we engage with, learn from, and work more closely with policy makers, teachers, principals and other education workers about what research is needed

- how can our research contribute to teacher professional development

- how can this research be translated and impact on those who

- determine policy

- implement policy, i.e. teachers and principals

CoEDL has a wealth of experience in its researchers and projects, and can play an important role in this space. It was great to network with so many keen and interesting researchers, and we look forward to seeing where this discussion takes us next.