Investigating the use of Creative Commons licenses with Indigenous language materials Northern Institute, Charles Darwin University

March 29-30, 2016

Workshop report

Thanks to a small grant from the Faculty of Law, Education, Business and Arts (LEBA) at Charles Darwin University, granted to the Northern Institute (Cathy Bow) and the School of Law (David Price), an expert in the area of Copyright law and Creative Commons was invited to facilitate a two-day workshop in Darwin in March.

Our invited guest, Dr Anne Fitzgerald is a barrister who has practised, taught and researched in the areas of intellectual property law, internet/e-commerce law and international trade law for more than 20 years. She was a key part of Creative Commons Australia’s engagement with the Australian public sector, which resulted in Creative Commons licences being adopted as the default copyright licence by the Australian federal government. On this visit to Darwin, Anne was accompanied by another experienced IP and crown lawyer, Neale Hooper, who has also been heavily involved in the Australian arm of Creative Commons and its implementation across government departments.

Workshop participants were invited from partner agencies of the Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages project (Northern Territory Library, NT Department of Education, Batchelor Institute, CDU Library), as well as other interested parties (ACIKE, ARDS, SIKPP (Yolngu Studies), iTalk Library, NAAJA, Northern Institute). There were 23 participants on Tuesday and 16 on Wednesday.

Dr Fitzgerald presented a helpful overview of Creative Commons (CC) and the six CC licenses available, and how they align with copyright law and facilitate the remix and reuse of digital materials. There was information about how the licenses have been used across different sectors in government and research, and some cases where the validity of the licenses had been tested and approved. There was a demonstration of some of the tools available for facilitating the use of CC licenses and appropriate attribution. David Price from CDU’s School of Law gave a useful overview of copyright law and how it relates to Traditional Knowledge (TK) and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP), which was highly relevant to the participants.

The remainder of the workshop focused on specific case studies, where participants were able to share from their own experience some of the challenges and concerns they have about using CC licenses. Cathy Bow shared in detail about the Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages, and the challenges involved in the decision to use a CC-BY-NC-ND license to promote engagement with the materials while respecting their integrity. Kerry Blinco from NT Library presented on their Community Stories project, and tried to separate some issues which are often grouped together, such as copyright, moral rights, ICIP, conditions of use, access control (secret/sacred/sorrow), cultural warning and metadata. Hannah Harper from ARDS presented on the importance of developing a shared vocabulary to discuss issues of ownership and copyright with Yolŋu people, before presenting a particularly interesting case about a film project which raised some thorny issues about ownership and IP. Karen Manton from Batchelor Institute spoke about the CALL collection and their focus on preservation, access, growth, promotion, and supporting community activities to preserve, maintain and revive culture and language practices. She identified some of the concerns they face in the digitisation project and the website project, and their reasons for not using Creative Commons, in order to include specific protocols.

The discussion of specific projects and issues was most helpful, as it connected the general issues of CC and copyright law to specific practices, and the input from two very experienced lawyers in this area was most valuable. There is room within CC licensing to include reference to specific protocols for respecting ICIP, however these protocols are not enforceable by law. Both Anne and Neale pointed out that practice often precedes policy, as was their experience with the implementation of CC licensing with public sector information leading to official announcements about open data in government. As our projects establish best practice, we can create new norms which can then influence government policy. It was agreed that the discussion about these issues should continue, with plans for a conversation circle to meet regularly to enable ongoing work in this space. There is potential for a larger project exploring how this may happen on a wider scale.

In addition to the two-day workshop, Dr Fitzgerald also presented a public lecture as part of the Open Territory program, hosted by Northern Territory Library and sponsored by the Northern Institute. The audience came from business, government and education, and were given an overview of how different sectors have used CC licensing to enable the opening of huge quantities of data, and the benefits of this across a number of areas.

Thanks to our presenters, Anne Fitzgerald and Neale Hooper, and all the workshop participants for an excellent event. Special thanks to LEBA for the small grant funding which allowed the event to occur, and to the Northern Institute for their support and assistance.

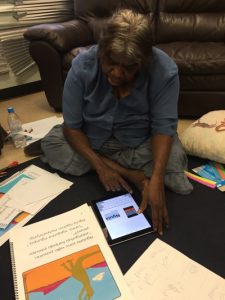

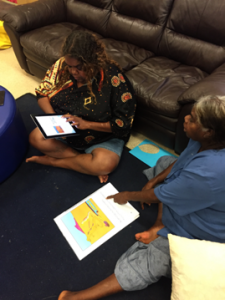

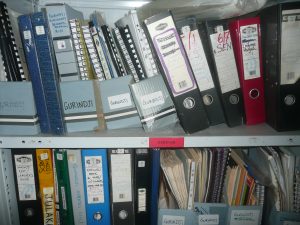

The Katherine Regional Aboriginal Language Centre was a hub of linguistic activity from 1991 to 2010. Run by the Diwurruwurru-jaru Aboriginal Corporation, it served all the Indigenous languages of the Katherine region, creating resources and running teaching programs in schools. All the materials in the library have been locked away since the centre closed in 2010, under the auspices of Mimi Arts, and last week a team from CDU (Cathy Bow and Trish Joy) and Western Sydney University (Sarah Cutfield) had the opportunity to audit the collection for archiving purposes.

The Katherine Regional Aboriginal Language Centre was a hub of linguistic activity from 1991 to 2010. Run by the Diwurruwurru-jaru Aboriginal Corporation, it served all the Indigenous languages of the Katherine region, creating resources and running teaching programs in schools. All the materials in the library have been locked away since the centre closed in 2010, under the auspices of Mimi Arts, and last week a team from CDU (Cathy Bow and Trish Joy) and Western Sydney University (Sarah Cutfield) had the opportunity to audit the collection for archiving purposes.

David P. Wilkins, PhD

David P. Wilkins, PhD