The Western and Northern Aboriginal Languages Alliance (WANALA) biannual forum was held in Batchelor on 17-18 October 2018. It brought together interested people from language centres around WA and the NT, as well as some other interested parties. One of the streams focused on collections management, which is always a challenge for language centres. There are many technical issues (which of the myriad tools available are appropriate for which context? How to weigh up usability, price, functionality, support required and rapid turnover?), funding issues (there is rarely funding available to support the time and human resources required for appropriate collection and archiving of precious language resources) and intellectual property issues (language centres are answerable to the communities they serve, while also managing compliance with national laws, negotiating the balance between open sharing and careful restriction). This workshop was an excellent opportunity for people to come together and share ideas about all these issues in a supportive, friendly environment.

The Western and Northern Aboriginal Languages Alliance (WANALA) biannual forum was held in Batchelor on 17-18 October 2018. It brought together interested people from language centres around WA and the NT, as well as some other interested parties. One of the streams focused on collections management, which is always a challenge for language centres. There are many technical issues (which of the myriad tools available are appropriate for which context? How to weigh up usability, price, functionality, support required and rapid turnover?), funding issues (there is rarely funding available to support the time and human resources required for appropriate collection and archiving of precious language resources) and intellectual property issues (language centres are answerable to the communities they serve, while also managing compliance with national laws, negotiating the balance between open sharing and careful restriction). This workshop was an excellent opportunity for people to come together and share ideas about all these issues in a supportive, friendly environment.

The first morning involved presentations from language centres about the issues they face. Julie Walker shared the Wangka Maya experience, having been incorporated in 1987 but not having an archive when she started in 2013. This meant there was no system in place for managing the collection of books, recordings and files produced in languages of the Pilbara over many decades. A fire in the building led to smoke damage that destroyed over 5000 cassettes, which in turn affected relationships in the community. A significance assessment and conservation assessment led to recommendations for disaster planning, and they outsourced a South Australian company to digitise their collection. She noted that specialist support is very hard to find in remote contexts, making it incredibly expensive to build and support appropriate infrastructure, and long distances between communities means that workshops need to be carefully planned – laptops running out of power hundreds of kilometres away is a problem not faced in our major cities. The language centre faces many requests from community members to access materials, so detailed metadata is required, which also linked to physical or digital locations – knowing something exists is not the same as being able to show it to someone.

David Nathan from the Groote Eylandt Language Centre reported on the development of a database that responds to the need for a repository for the huge amount of materials produced over many years which had never been systematically collected or catalogued. He noted that the most important knowledge about the materials is not in the system or metadata but in the community itself. The Ajamurnda database is designed to bring together the two components – digital resources and the local knowledge about them. He noted the importance of a collections policy to assist with the selection and curation of files, the use of software to automate some of the processes, and the benefit of using unique file IDs in managing long file names. They developed a range of access protocols that allow people to feel safe about looking at things and about what other people are looking at, coming up with 7 categories which are currently being tested, with a view to creating a living map of knowledge circulation.

Daryn McKenny from Miromaa Aboriginal Language & Technology Centre reported on how they’re managing both the physical and digital collections they’ve developed over many years, including some very rare historical documents about the languages of the Newcastle area. He described the different processes used for capturing and storing metadata, as well as various means of mirroring and backing up. He showed the Fujitsu Scan Snap, a handheld scanner with a range of software that makes digitisation look very simple. He also identified some of the challenges of keeping a physical collection safe, and recommended some useful software and tips that not-for-profit agencies can benefit from.

Presenting online, Mari Rhydwen from Muurrbay Language Centre shared a different perspective, as they don’t create much new material but need to keep safe existing material. They use Dropbox to store files, but acknowledge that this is not ideal. There were also concerns about security and access, for example if computers are damaged or stolen, or if someone with a large collection passes away. Looking to the future, if the language centre did not exist, what would happen to all these materials?

Siobhan Casson from the Kimberley Language Regional Centre in Halls Creek showed images of their archive room in the centre of their building, and how their material has been carefully catalogued over the years, earning high praise for their collection in a Significance Assessment in 2008. The difficulties have been in maintaining this high standard, with turnover of outside staff, lack of committed funding to this aspect of the centre, and the lack of links between the digitised materials and the database. The challenge of working in a language context with no embedded literate culture means some materials like grammars and dictionaries are not the most appropriate for supporting intergenerational language transmission, yet funding opportunities tend to prioritise text-based resources rather than teaching on country programs. She proposed an information management system that could incorporate the digital archive as part of a larger infrastructure, and they are looking for how this might be done effectively.

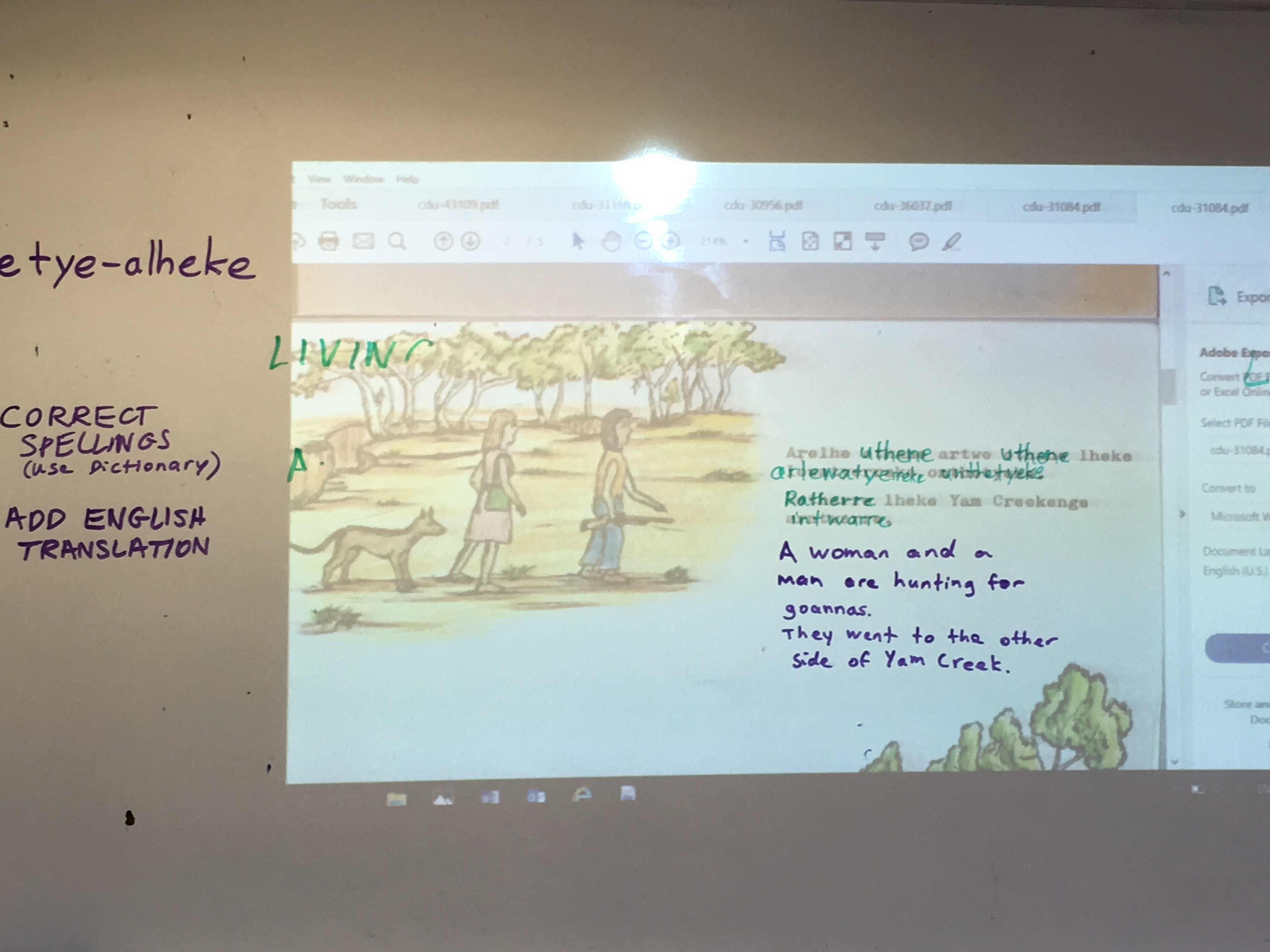

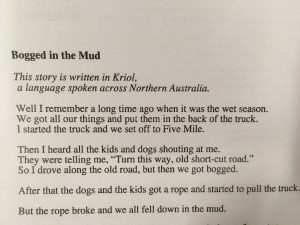

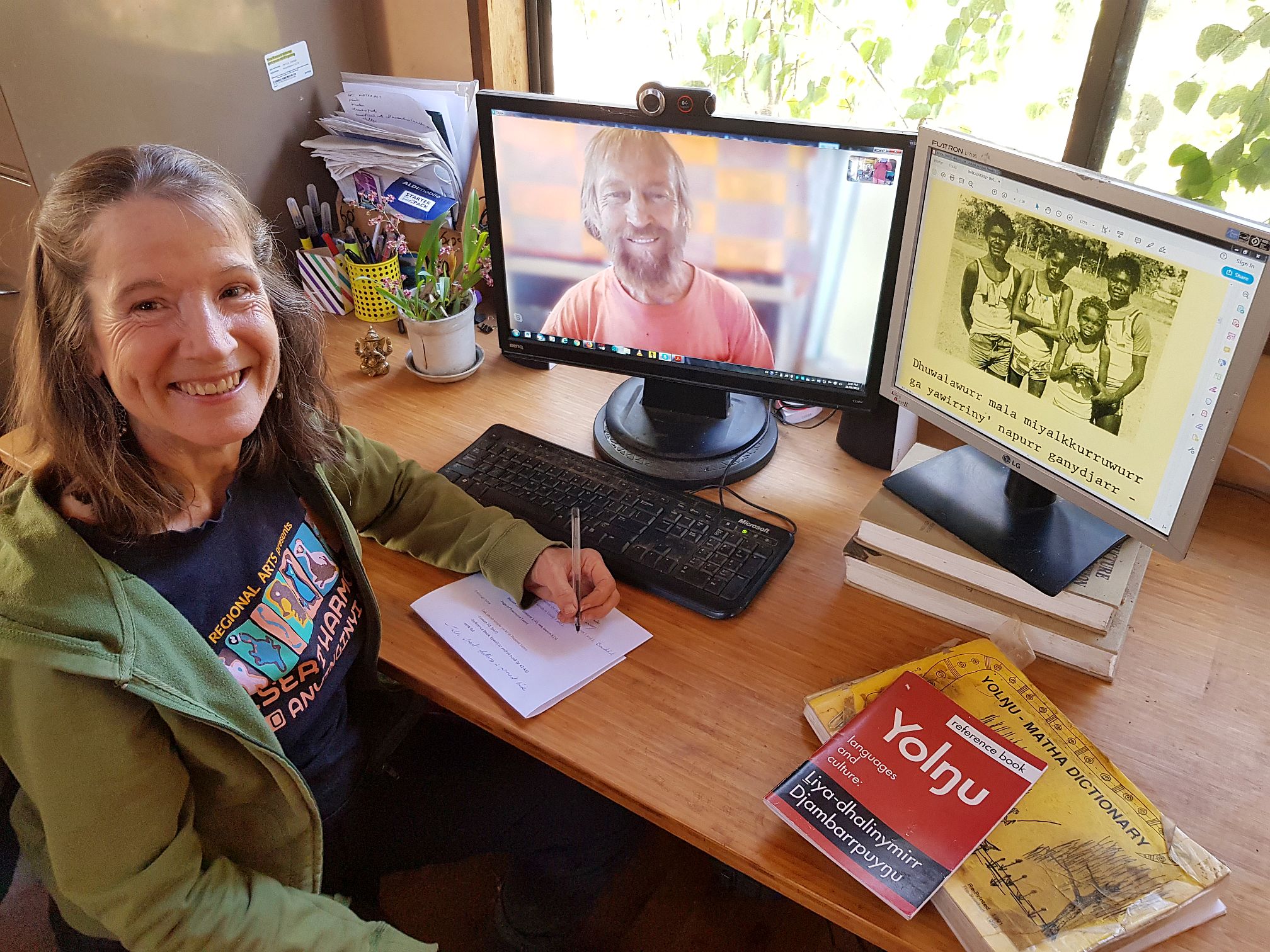

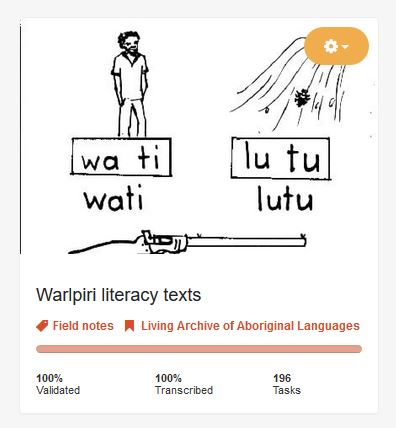

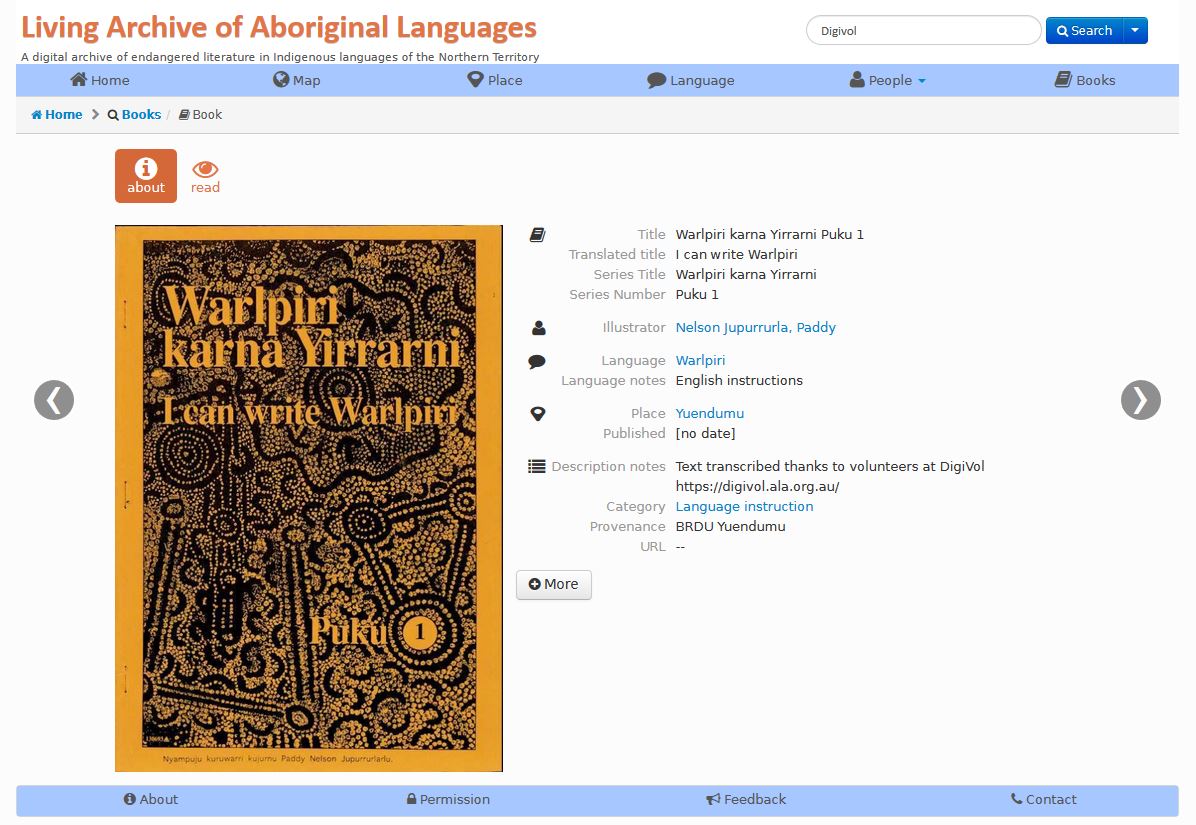

After hearing from the language centres, the next sessions focused on institutional archives and how they can support the work of language centres. Cathy Bow from Charles Darwin University presented on the Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages, a digital collection of endangered literature in languages of the Northern Territory. A collaborative partnership funded by the Australian Research Council, the archive contains around 5000 items in 50 languages. The collection is stored on the university’s library repository, in PDF and text form for presentation, and TIFF formats for preservation, available through a visual website that requires little text or technical literacy to navigate. She described the way tensions between copyright and Indigenous cultural and intellectual property are being managed, through licenses, permission forms and take-down notices, while using a Creative Commons license to inform users of the conditions under which the materials are shared.

Karen Manton from the CALL Collection at Batchelor Institute acknowledged the importance of the people whose work form the basis of their national collection, and how seriously they take the responsibility of caring for these materials. They have developed an extensive database and have been digitising their collection, with first stage of their website now available. With help from Terri Janke, they developed a range of end user licenses and protocols which inform and protect both the creators and users of the collection.

Amanda Harris from PARADISEC described nearly 50 Tb of files from 99 countries and over 1000 languages, which has now spread well beyond the Pacific region. Their custom-built database promotes discoverability, and where possible embeds metadata directly into files. She discussed some of their strategies of enriching metadata, by inviting language experts and community members to add value to the collections, as well as activities to promote the collection such as a Virtual Reality event at Canberra Museum in 2017. Their collection includes materials form Australian languages and they are pursuing partnerships with language centres to support local archiving activities.

In the panel discussion time, Steven Bird from CDU shared a 2010 checklist for language archives which focused on the key issues of audience, access, preservation, sustainability, but noted that issues of relevance to Indigenous Australia should also be included, such as cultural protocols. It was noted that the intertwining of technology and human resources is often under-estimated – a language centre may get funding to buy or build software, but the cost of a staff member to research, install, maintain and train others in using this is not always factored in by funding bodies. There was a clear indication that language centres wanted to manage their own collections, not relying on external experts who leave without building capacity for ongoing local sustainability. It was noted that collections and archives are not exactly the same, with daily management of materials often demanding more immediate attention than the safe storage and backup of archival materials. David Nathan urged caution about use of the word ‘archive’ to mean all sorts of other things – collection, library, website, backup, server – which don’t necessarily conform to the requirements of an actual archive. Steven Bird noted that technology is only one part of the process of information management, and noted that the federal government’s commitment to technological solutions, as articulated at the National Indigenous Languages Convention on the Gold Coast earlier this year, needs to be challenged. The current forum is an opportunity to articulate what is required and how the government can support the vital work of language centres, with the UN’s International Year of Indigenous Languages in 2019 an ideal opportunity to become more visible and more vocal in our efforts.

In the workshops after lunch, small groups worked on specific topics, such as Access, Planning, People and Skills. The planning group focused on knowing where to start, such as with an audit of what materials there are and in what forms, which can then be used as the basis for a database, whether a simple spreadsheet or a more complex system. A suggestion that the government could provide storage for off-site backup for language centre materials was met with caution from those who don’t trust the government to do this, although some agreed that AIATSIS would be a suitable repository. Prioritisation of work is also crucial, thinking internally, regionally, and nationally, with a view to sharing knowledge and avoiding duplication of effort. Both the audit and prioritisation processes require funding and time and people, which are all in short supply in language centres. There may be some crowdsourcing or volunteer options, though these may require some initial setup. First Languages Australia could support the process by providing case studies, guidelines and factsheets, if people are willing to share what they have. There was some concern about language becoming a product that can be packaged, so the need for more innovative ways to think about collections and data as something other than artefacts to be managed, and to communicate the value of our languages (in all their forms) for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

The final session of the day involved discussion of tools. Susan Locke from First Nations Media Australia (formerly IRCA) described their multifaceted approach to developing resources and standards, and their coordinated approach to a national community collections plan. They are working on an affordable digital asset management system (DAMS) for Indigenous media organisations which would manage preservation files for archiving, managing ‘mezzanine’ files for production house purposes, managing community viewing and listening, capturing cultural information, and controlling access according to cultural protocols. This work will begin in 2019 but requires additional funding.

Anja Tait from Northern Territory Library asked us to reconsider ‘what is a library’ as she described their 32 remote library services, plus providing wifi to 44 communities. She described some legacy projects – a language app, bilingual board books – as well as an innovative rethinking of how to classify library materials in a community environment. They’re currently in the process of reconfiguring the Community Stories service, which enables local communities to store and share photos, videos, texts, etc. under local authority. The library is considering how best to serve the local and regional needs of communities, and Anja ended with a statement on the importance of trust.

Daryn McKenny shared about extensions to the popular Miromaa software, which will include the capacity to manage collections for language centres. The update will allow users to manage multiple databases through a single interface, and each database can have its own security or cultural protocols attached. It will also be customisable, so users can create their own fields and tags, and allows storage of digital artefacts within the system, directly linked to the metadata.

On Thursday, continuing talk of tools, Nick Thieberger from the University of Melbourne shared 3 emerging projects happening through CoEDL. The first is a multi-platform extension of SIL’s SayMore program to assist users to enter catalogue information when creating collections, allowing simple means to view and add information about files, people, places, etc. The second is a collections database for small agencies, allowing language centres and others to create rich metadata to keep track of their collections. The third is based on the Digital Daisy Bates project, as a map interface to collections, where a user can click on a map location to see a text, and the text and images scroll together. They have funding for each of these projects and are looking to partner with language centres to explore them further.

The discussion part of the workshop covered many different areas, from a warning about talking only about ‘tools’ but rather thinking in terms of ‘concepts’, to a call for Miromaa to become the tool that all language centres use. Miromaa is already used widely, but is not sufficiently funded to meet the needs of all its users, with Daryn providing the majority of support directly. There is a sense of urgency about these issues, with people wanting more opportunities to workshop and discuss options, even before the next Puliima conference in August next year. First Languages Australia has a project researching the tools used by language centres, which can inform ongoing work in this space. It was decided that an important outcome of this workshop would be a statement from WANALA calling on the government to acknowledge the importance of Indigenous languages and to support them through adequate funding and legislation. A team is currently working on this statement.

The remainder of the day involved presentations from the other workshops happening over the forum, including Message Sticks, language in Art, Storytelling, and the use of drones to document country – fantastic footage from nearby Litchfield National Park. All the attendees left excited by the inspiring workshop, and looking forward to the next steps.

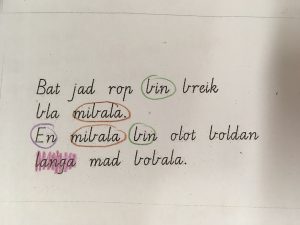

Greg Dickson and Gautier Durantin from the Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL) have published an academic article on their research on Kriol and its different dialects. They researched one particular Kriol word called the reflexive, which is like the English word ‘myself‘. They looked at how this word might be spoken differently by Kriol speakers in different communities.

Greg Dickson and Gautier Durantin from the Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL) have published an academic article on their research on Kriol and its different dialects. They researched one particular Kriol word called the reflexive, which is like the English word ‘myself‘. They looked at how this word might be spoken differently by Kriol speakers in different communities.

One of the unique benefits of Charles Darwin University is being able to work on Aboriginal languages on-campus, with speakers who live right here in Darwin. In August 2018, I invited Murrinhpatha speakers Erica Bangun and Mary-Ann Jongmin to the

One of the unique benefits of Charles Darwin University is being able to work on Aboriginal languages on-campus, with speakers who live right here in Darwin. In August 2018, I invited Murrinhpatha speakers Erica Bangun and Mary-Ann Jongmin to the