Jo Cilento from Queensland shares her story of using the materials in the Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages

The Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages is a wonderful resource. How I would have loved to have had access to such a treasure as a child! From an early age, I had an intense interest in the languages and cultures of Australia’s First Nations peoples. My interest was so strong that at the age of 11 I seriously contemplated running away to Central Australia to join the Arrernte people.

I longed to be fluent in an Aboriginal language. But throughout my childhood, the only book on Aboriginal languages that I could find was a miniature dictionary called ‘Lilliput Aboriginal Words of Australia’. Even though it contained words from many different Aboriginal languages rather than a single language, it became my constant companion. I memorised all the words that it contained and their meanings.

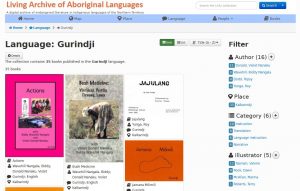

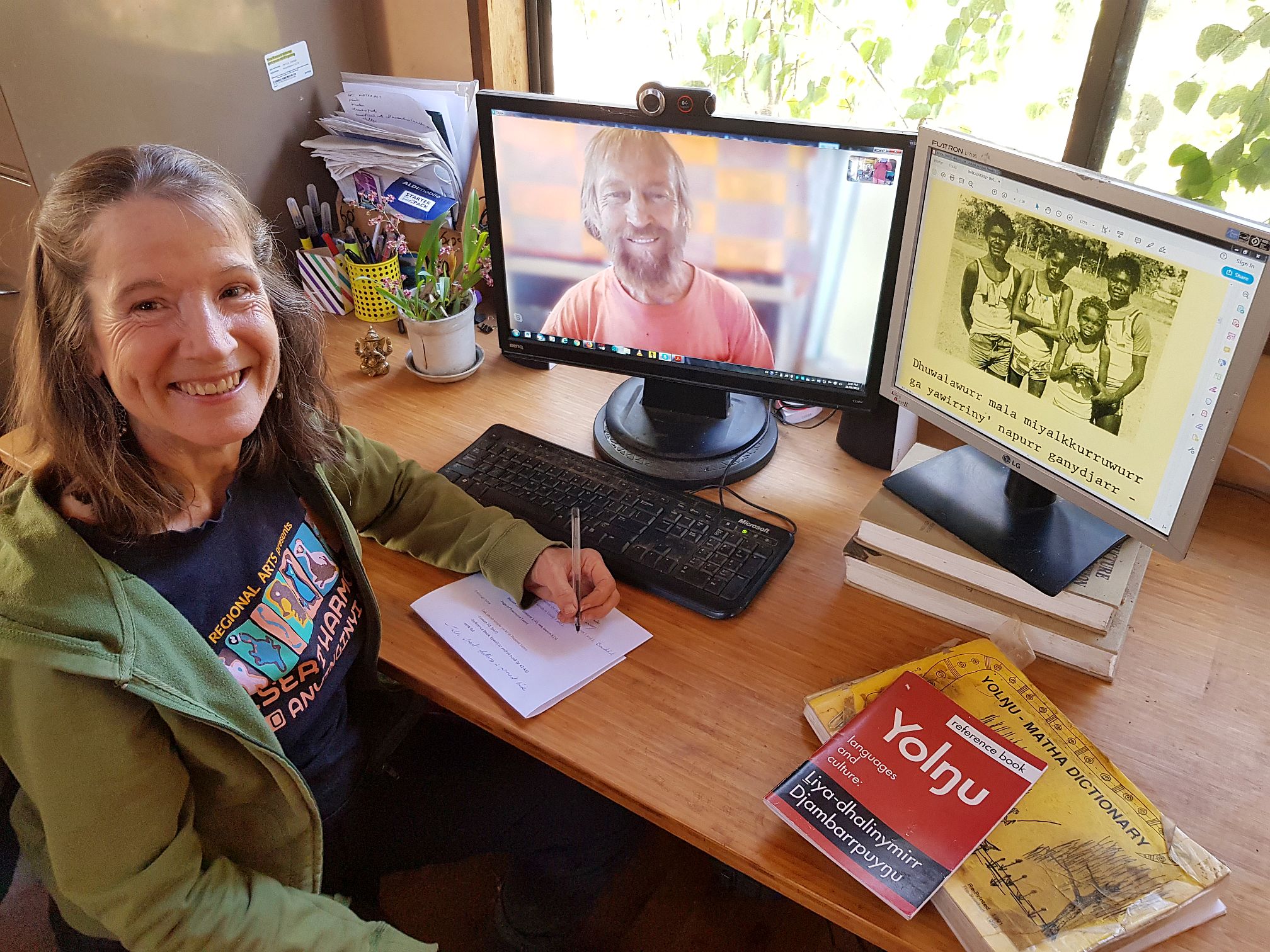

I was first introduced to the Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages while working as a tutor in the languages and cultures of the Yolŋu peoples of North-east Arnhem Land for the Yolŋu Studies Unit, at Charles Darwin University. I spent many happy hours, reading through the various Yolŋu language book collections, just for the sheer pleasure of it. I encouraged my students to investigate the collections as well, as I knew that their language acquisition and understanding of the differences and similarities of the various Yolŋu languages they were exploring in their courses would be greatly enhanced by doing so.

But it wasn’t until I began giving private one-to-one online lessons in Djambarrpuyŋu (the lingua franca of the western part of North-east Arnhem Land) and other related Yolŋu languages, that I actively began incorporating the books from the Living Archive in my teaching. Most people I teach in these sessions are keen to learn Djambarrpuyŋu before heading out on cultural tours to remote homeland communities in North-east Arnhem Land, where English is not the main language, but perhaps the fourth or fifth. One such place where cultural tours are conducted is Mäpuru, where the participants deepen their cultural understandings by being fully immersed in the daily activities of the community for 10 days.

There are very few resources for teaching Djambarrpuyŋu, so having access to the books in the Living Archive has become an essential and enjoyable part of the way I teach my students. From the very first lesson, I incorporate books that are relevant to whatever grammatical structure I may be teaching in that session.

For example, Djambarrpuyŋu uses the suffix –ŋur which is added to a noun to create an adverbial expression of place (in English we use a preposition such as in, at, on or by to express the same thing). When I introduce this concept to students, we look at selected stories online where this structure is particularly prominent. The archive includes a series of readers for Yolŋu children with repetitive sentences and simple drawings, which demonstrates these forms clearly. There are stories with verbless sentences, such as Weṯi, wanha nhe? (Kangaroo, where are you?), and others with the verb in present continuous tense, such as Ŋarraku ŋathi dhuwal (Here is my grandfather). Stories such as these give the student the chance to see the grammatical structure used several times in a story context, rather than simply in the isolated sentences I would have given them as examples.

To reinforce their learning, I also assign homework to read books from the Living Archive that contain the grammatical structure/s they have learned that session. My students have all reported that the books are a valuable aid to their learning. They really enjoy the challenge of translating the stories by themselves, and have said that it adds to the fun of learning. The process also helps them to embed the grammatical patterns they have been learning, and gives them the opportunity to learn new vocabulary used in context.

Many thanks to everyone who has been involved in this project. It is an invaluable resource for not only the present generations, but also the future ones.

We love hearing stories about how people use the materials in the Living Archive! If you would like to share your story, please contact us!

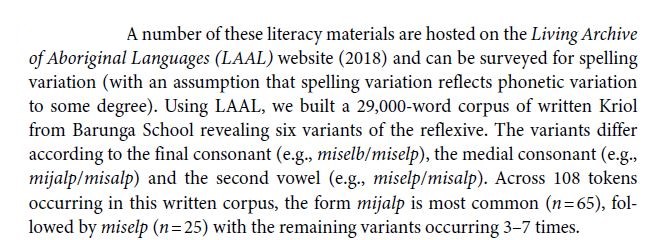

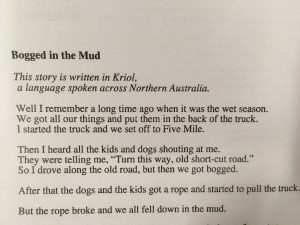

Greg Dickson and Gautier Durantin from the Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL) have published an academic article on their research on Kriol and its different dialects. They researched one particular Kriol word called the reflexive, which is like the English word ‘myself‘. They looked at how this word might be spoken differently by Kriol speakers in different communities.

Greg Dickson and Gautier Durantin from the Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL) have published an academic article on their research on Kriol and its different dialects. They researched one particular Kriol word called the reflexive, which is like the English word ‘myself‘. They looked at how this word might be spoken differently by Kriol speakers in different communities.

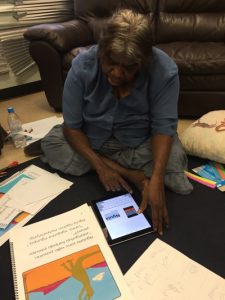

One of the unique benefits of Charles Darwin University is being able to work on Aboriginal languages on-campus, with speakers who live right here in Darwin. In August 2018, I invited Murrinhpatha speakers Erica Bangun and Mary-Ann Jongmin to the

One of the unique benefits of Charles Darwin University is being able to work on Aboriginal languages on-campus, with speakers who live right here in Darwin. In August 2018, I invited Murrinhpatha speakers Erica Bangun and Mary-Ann Jongmin to the

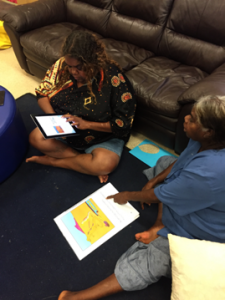

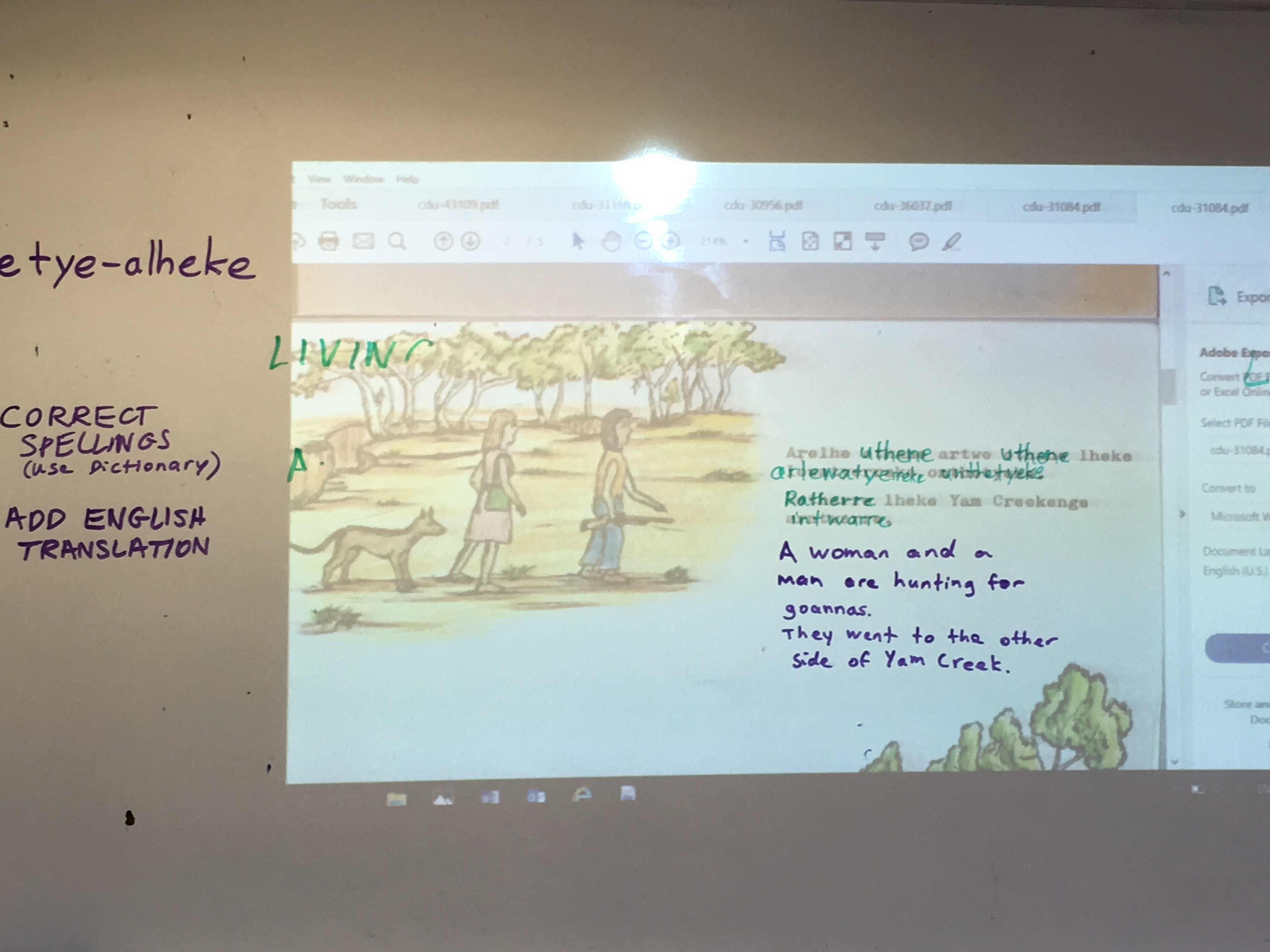

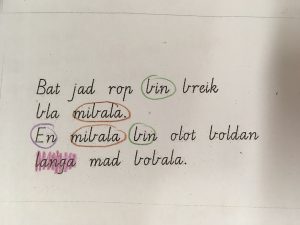

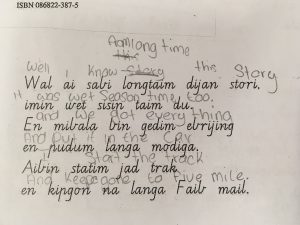

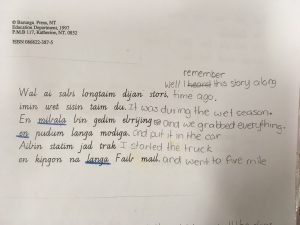

The students all seemed attracted to different tasks but were all engaged. One student colour coded a number of words – colouring all the same words one colour and working out what those words were. Although they all translated one or two sentences, one student enjoyed going on with this and worked hard to write down translations for the whole text. I could see from his writing that he struggled to notice when articles and prepositions were needed in English. Another student was not keen to write but orally worked on translations with me. She was able to switch easily to the correct use of articles and prepositions.

The students all seemed attracted to different tasks but were all engaged. One student colour coded a number of words – colouring all the same words one colour and working out what those words were. Although they all translated one or two sentences, one student enjoyed going on with this and worked hard to write down translations for the whole text. I could see from his writing that he struggled to notice when articles and prepositions were needed in English. Another student was not keen to write but orally worked on translations with me. She was able to switch easily to the correct use of articles and prepositions.